In 1867 the New Zealand Armed Constabulary was formed - essentially an army of occupation - to replace the regiments, and the small volunteer and Militia units, and as part of the Self Reliant policy of the new Premier of NZ, the Honourable Edward Stafford.

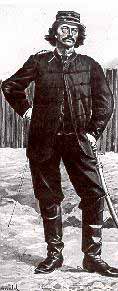

Von Tempsky had a division about the size of his Rangers, and ex-army men joined up with enthusiasm.

One of their first roles was a confrontation with Riwha Titokowaru, who had taken the Hauhau movement to a new militancy, including cannibalism.

While rebuilding the redoubt at Waihi, the Constabulary were attacked by Titokowaru, and Von Tempsky was later to face an enquiry - he did not take his cavalry to the defence of the redoubt.

Reinforced by recruits from Wellington, Lt/Col McDonnell attacked Titokowaru at Te Ngutu-o-te-Mana, sacking the Hauhau fortification, although the Maori leader managed to escape.

At Turuturu-Mokai, Titokowaru's warriors crept up on a group of settlers and Armed Constabulary led by Capt Ross, and over-ran them in the bush the Pakeha were only saved from total annihilation by a relief force led by Von Temspky.

With reinforcements from Wanganui, a Maori contingent loyal to the Crown, (called "kupapa"), McDonnell then took his force of around 800 men out of Waihi, and arrived back at Te Ngutu o te Manu, which had been reclaimed by the Hauhau.

Circling through the surrounding bush, the inexperienced Wellington recruits were soon being annihilated, and McDonnell ordered a retreat - Von Tempsky was in charge of the rearguard.

A shot to the head instantly killed Von Temspky, and many took the credit for firing the weapon that ended the life of this remarkable globe-travelling colonial.

The few remaining survivors dragged themselves back to Waihi, and McDonnell was in disgrace - however he blamed his new recruits for the disaster.

A new commander arrived in Taranaki in 1868, Lt/Colonel Whitmore (below), and assembled a force at Wairoa (present day Waverley) to confront Titokowaru.

Marching into the bush they were totally outflanked and outgunned by the rebel warriors at the Battle of Moturoa, led by their able and wily tactician.

Defeated, Whitmore withdrew to the Bay of Plenty, and there arose a fresh challenge.

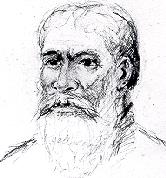

Te Kooti Rikirangi, a young rebel, had escaped from what could have been lax confinement on the Chatham Islands. His internment there was questionable - without trial, he and hundreds of other "troublemakers" had been seized in the Bay of Islands, and summarily shipped to a cold, windswept place.

He had taken control of the ship "Rifleman" and forced it to sail back to New Zealand.

In all, 163 men, 64 women and 71 children escaped. He disappeared into the bush in the Uruweras.

Whitmore's men were exhausted after being thrashed by Titokowaru, and a long march across the North Island, and waited for reinforcements before heading out to look for Te Kooti.

Titokowaru was safe in his Taranaki bush for now.

Whitmore, reinforced in mid-winter 1868, set out after Te Kooti, and found him at Ruakituri River. The skirmish was undecisive, but Te Kooti (below) was wounded.

After the deaths of four Europeans at Whataroa, Major Lambert then began the search for the Maori warrior.

He didn't have to look far - a lightning raid on Poverty Bay by Te Kooti caused the deaths of Major Biggs, his family, and 70 other Pakeha.

Whitmore returned to Wanganui, but sailed back to Poverty Bay later that year with a force of Armed Constabulary.

Te Kooti had built a pa at Ngatapa, and Whitmore lay siege, circling the pa, apart from a cliff-face deemed impossible to use.

It was strategically a disaster for Te Kooti, because faced with starvation, and not willing to surrender, he had to fight his way out or flee. He fled, urging his people down the cliff-face, but was doggedly followed into the bush by Major Ropata with his Ngati Porou and Arawa soldiers, who killed a great many of the fleeing warriors.

Te Kooti however escaped, and believing that he was no longer a threat, Whitmore returned to Wanganui, arriving in 1869.

Ropata was rewarded with rich Bay of Plenty land, ironically the land that Te Kooti was trying to recover.

Titokowaru meanwhile, who now had a £1,000 bounty on his head, was threatening to sack Wanganui, and had built a new pa at Tauranga-ika, near Kai-iwi. Whitmore then encircled it, and his troops sang through the night, waiting for their attack at dawn - the Maori defenders enjoyed this entertainment so much they called for encores.

The next day, Whitmore moved up on the pa, and it was deserted. Titokowaru and his warriors had slipped away in the night.

Later, it was discovered that within the pa, Titokowaru had tried to obtain another's wife, and his sudden loss of mana caused a refusal of his chiefs to obey him. Because he had also been a kaumata, or spiritual leader, he became no longer "tapu" or sacred. This double loss reduced his stature to such an extent that he would simply not be followed.

Whitmore set off in pursuit of the Maori, through Patea and to Te Karaka, but he never did lay his hands on Titokowaru. The Maori chief never fought again, but did appear at Parihaka further north, in the 1880's with Te Whit and Tohu.

Te Kooti meantime, struck again in Opitiki, killing a European surveyor and then attacking Te Poronui, near Whakatane.

Only three men, and three women, were there to defend themselves, but it was two days and nights of warfare before Te Kooti's men killed them.

Te Kooti then moved on to a local kupapa pa at Tauporoa and sacked it, then followed up with the destruction of Whakatane itself.

He then moved through the bush to Mohaka and killed almost everyone there, chasing the survivors to Te Huke pa, which he also overran, and on to Hiruharama, which teetered on the edge of destruction as well. It was saved by Trooper George Hill, with volunteers, who rushed to their help.

Te Kooti disappeared again into the bush

The land wars, apart from Taranaki, were nearly finished by now, but faced with the guerilla-style of war being fought by Te Kooti, the NZ Armed Constabulary had learnt counter-guerilla skills.

The Arawa tribe formed a unit, called the Arawa Flying Column, and proved to be very successful.

Halfway through 1869, Whitmore landed his troops in Tauranga, and they set off for Matata, eventually fighting their way to Ahikeruru ( now Te Whaiti ) - they were discovered encircling the pa, and the men fled, leaving the women and children who were captured, all unhurt.

Te Kooti's men again disappeared, and Whitmore returned to a base at Fort Galatea, passed command to Lt/Col St John who was a veteran of the Crimea, and went to Wellington.

St

John took his small force out towards Taupo, and camped at Opepe, which Te Kooti

discovered and attacked. Nine men died, and four escaped.

The NZ Armed Constabulary

eventually retired back to Tauranga.

Te Kooti then sought the aid of Rewi Maniapoto, to kill the Arawa and Ngati Porou on the East Coast - and drive the Pakeha into the sea.

Maniapoto declined, and Te Kooti went to Te Porere, near Taupo, where he built a pa. Learning of this, Lt/Col McDonnell, who was being given a chance to redeem the disgrace at Wanganui, assisted by kupapa and Constabulary, attacked the pa.

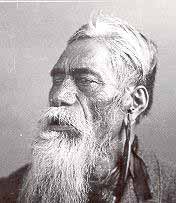

Renata Kawepo (below), a chief who fought alongside the Government forces, lost an eye to one of Te Kooti's women warriors.

Te Kooti was again wounded, but again escaped.

The NZ Minister for Defence, and also for Native Affairs at that time, was Donald McLean. His views were completely different to Governor Grey's, that there could be any justification in fighting a war for land.

McLean formed an alliance with Rewi, who then tried to encorage Te Kooti to stop fighting. Te Kooti could or would not.

Another envoy approached Te Kooti at Matamata, a settler named Firth, with an offer of a ceasefire - Te Kooti dreaded becoming a prisoner, and possibly being executed, so again refused.

There were a few more skirmishes with the Government, seeing Kereopa captured and tried, until eventually Te Kooti simply stopped fighting - in 1872 he was pardoned, and retired to the Ohiwa Harbour.

Attorny-General Prendergast had proclaimed that the rules of war 'between civilised nations' did not apply to Maori, that "there can be no doubt that all who have taken part in it have forfeited all claims to mercy'.

At least there is this to remember, that the British solution to the troublesome native was not so totally, so grandiosely, and so grotesque as their 'final solution' arrived at, across the Tasman Sea in the new colonial Australia: that the Tasmanian Aborigine was to be killed to the last person.

As an historical aside here, James Stephen, under-secretary of the Colonial Office had written to the Australian Governor, Gipps, in 1838,

“The causes and consequences of this state of things are alike clear and irremediable nor do I suppose that it is possible to discover any method by which the impending catastrophe, namely the extermination of the Black Race, can long be averted.”

and in 1838, (100 years of course before the German Nazis embarked on a similar campaign of genocide),

“The tendency of these collisions with the Blacks is unhappily too clear for doubt. They will ere long cease to be numbered amongst the Races of the Earth. I can imagine no law effective enough to avoid this result ... All this is most deplorable but I fear it is also inevitable. The only chance of saving them from annihilation would consist in teaching them the art of war and supplying them with weapons and munitions—an act of suicidal generosity which of course cannot be practised.”

Truganini, the last native woman, died in 1876, and for 50 years her skeleton was hung on display in the Tasmanian museum.

The Maori resistance and deeply-ingrained warrior culture, as well as reasonably balanced force of numbers may have saved them from total extinction.

At this time a chief's head earnt a bounty

of £10 and a warrior's head £5, possibly as a result of the Wellington

Independant's editorial that had admonished

"..no mercy should be shown. No prisoners should be taken. Let a

price be put on the head of every rebel, and let them be slain without scruple"

The Land wars were ending.

It might be misleading to imagine that there were now thousands of European landowners however - it has been observed that by the end of the 1870's only 250 Pakeha owned, collectively, seven and a half million acres. ('Ask that Mountain', Dick Scott, 1975)

The Government was still under enormous pressure to acquire more land.

The NZ Armed Constabulary now split into two groups, the Militia and the Police - becoming eventually the NZ Army and the NZ Police.

Ten years later, Maori led civil disobedience at Parihaka (next page), under Te Whiti and Tohu, which in later years would severlely embarrass Pakeha - and it was not until 1916 that the final gunshots would be exchanged between Pakeha and Maori, when the Prophet Rua Hepetipa would call out "Enough - do not shoot" at Maungapohatu.

New Zealand.org.nz Homepage here